If you’re a trans person capable of becoming pregnant and that’s something you’re seeking to do, or if you’re already carrying a wanted pregnancy, you’re likely to have a list of immediate concerns. Some of those might be dysphoria associated with pregnancy, frustration over having to stop HRT or not go on it if that’s something you want, whether you’ll be considered a fit parent due to your transness, and how you’ll navigate antenatal healthcare. The issue I’m going to be discussing here is the last one. Pregnancy care varies in quality at the best of times, but when you’re trans and coping within a system that isn’t built for you it’s important to be proactive about self-advocacy.

First thing’s first, what are your goals?

To determine what it is worth pushing for based on the pros and cons, we need to assess your priorities.

If you are primarily concerned with how you will mitigate severe dysphoria during pregnancy which may otherwise be debilitating, your focus should be on avoiding misgendering and treating the pregnancy symptoms which draw your attention to parts of your body which cause you the most distress. On the other hand, if your main worry is the health of your baby because you’re higher risk or have anxiety regarding their safety, you may find that staying on good terms with the midwives and doctors by being more lax when correcting misgendering gets you the smoothest and fastest medical care.

Write down the things you want during your pregnancy, then add a mark next to the things you cannot cope without. When two desires are likely to conflict, such as wanting to learn about chestfeeding so the baby will get the immune benefits of it and also wanting to avoid classes or literature with heavily gendered language, you should picture yourself giving up one desire for the other and see which scenario feeds more tolerable.

Depending on whether you have medically transitioned to some extent, you may have the option of pretending to be cis and avoiding potential interpersonal transphobia. If you do this, you get the benefit of avoiding targeted transphobic comments or a bias against you, but only you can know whether the trade-off is worth it. There will be strongly gendered language everywhere and it’s more isolating than the closet usually is when you’re pregnant!

How to ensure continuity of care?

If you want to be certain that your level of care is consistent and that you’re not fearing wild transphobia every time you go to a prenatal appointment, on of the most beneficial options for you will be to ensure you see the same midwife or small group of midwives for all of your appointments. Personally, I ended up seeing a couple dozen midwives across my appointments during pregnancy and each had a different level of understanding of trans people and might engage in any level of hostility. Had I known I could insist on appointments with the same midwife each time, I would have benefitted immensely from not needing to explain myself over and over. I tolerated a lot of misgendering I shouldn’t have had to and midwives missed things that would have been caught if a smaller team had overseen my care.

You can also make a point of having mention of your transness added to your file in a way that is more obvious than it naturally would be. Even if you have gone through extensive medical transition, details about that will be scattered across lists of the medications you’ve previously taken and surgeries you’ve undergone. If it’s on the front page, no-one can miss it and you aren’t left wondering whether someone is misgendering you on purpose or not.

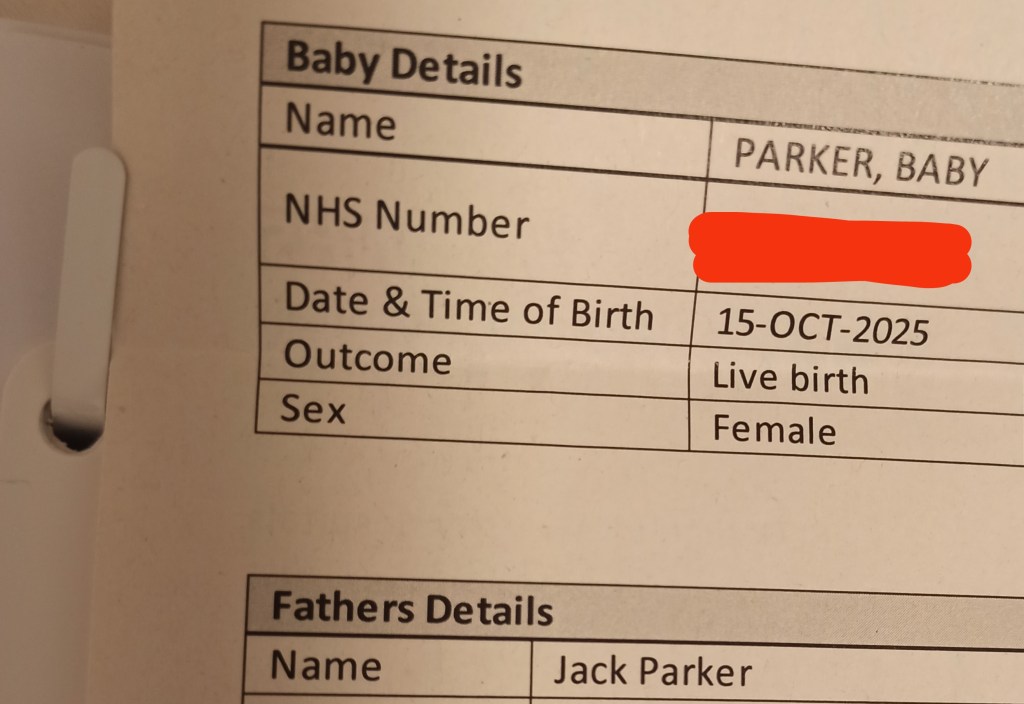

As you can see in the notes from my own hospital stay during labour and after birth, speaking to the first doctor who assessed me about my pronouns and gender meant that it was explicitly included in my file that was shown to all medical professionals tasked with my care.

I spoke with one of the midwives assigned to me after I had discussed the matter with my doctor and highlighted how important it was for me to be referred to as my daughter’s dad, and she was able to explain to me how the note left about my gender looked to other staff. She told me that it showed up on the first page as an alert, so each midwife assigned to me and any doctors I met with would have no excuse for not knowing.

Some people opt for having a doula or hiring a midwife privately, if they have the funds to do so, to guarantee that they’re guided through their pregnancy journey by someone who is supportive of trans people. Unfortunately you won’t have the same kind of control or ability to do background checks without seeking out private care.

How to respond to misgendering, or set boundaries around language use?

Corrections of misgendering should be firm, fast and specific. Once you start letting one midwife get away with it, it becomes a habit, so you ideally need to know whether you plan to be out as trans and insist on being gendered correctly during your pregnancy or not before you attend your first appointment. Be appreciative of apologies but don’t console your midwife if they ramble excuses – it’s not about them.

Bringing someone with you to your appointments who you trust and who does not struggle to use the correct pronouns for you can also make things a lot easier. Not only are you less likely to be mistreated when you have someone with you, but they can also model the correct behaviour when it comes to gendering you and make it less likely that the midwife or doctor uses the wrong pronouns or terms in the first place. Discuss in advance whether you’d like to be left to correct staff by yourself over any misgendering or if you’d prefer they did it for you.

When it comes to language you want used for your anatomy, you can also set boundaries around this and have the note added to your file. If you want to use terms like “front hole”, “chestfeeding” and others, you can explain the meanings and your healthcare provider should make an effort to use them. Be aware that literature you are given will still have the typical anatomical terms, so depending on your comfort level you may want to give them to someone else to read and have them relay it to you in language you prefer.

Forms you fill out at appointments are also highly likely to include gendered language or fail to account for trans people. They may include a selection of titles but only account for feminine ones and those linked to educational attainment like Dr. You can cross these out and write in your own title, like Mx. or Mr. manually and should not feel discouraged from doing so. Reports made through the hospital computers unfortunately cannot always be edited in the same ways, so they may include misgendering like describing the pregnant person’s name as “mother’s name” or including a sex category which is locked to female for all pregnant patients.

One instance of misgendering which may be unavoidable is related to registering the baby’s birth. In the UK and many other countries, the person who gives birth must be listed as “mother” on the birth certificate no matter whether they are trans or have changed their legal sex. Challenges have been made to these laws without success. Do not feel as though you have to capitulate to this when registering your child’s birth with how you refer to yourself at the appointment. You can call yourself the child’s parent or father, clarify that you are the one who gave birth, and agree that you understand you will be (incorrectly) listed as the mother without introducing yourself as such.

When to challenge recommendations impacted by your transness?

Arm yourself with knowledge about the ways that transition may impact your pregnancy. This could be from studies about the mental impact, whether you’ve exclusively transitioned socially or also sought medical transition. know what medical transition might effect and educate yourself, or more specialist medical information about how soon you can go back on testosterone after delivery. Your doctor is highly unlikely to know how HRT’s changes might carry over into pregnancy even after the hormones are stopped, meaning that the task of learning falls to you.

Those responsible for your care may be happy to follow your lead on what you need, or they may become offended that you presume to know more than they do on the topic even when it’s undoubtedly true that you do. Come prepared for hostility and print out information on the most important issues you are likely to face, so that you can back up your claims. Raise your concerns and state while you have them at the same time, like by mentioning worries about higher chances of tearing at the perineum because of vaginal atrophy.

If you have had top surgery, the kind you’ve gotten will impact whether or not you can chestfeed, however it is likely that midwives will default to giving you advice about it with the presumption that you are capable even if you have a visibly flat chest. They are very unlikely to know about your chances of being able to produce milk at all, let alone in a quantity that could reasonably feed your baby enough. Advice they give you about latching is also likely to be unhelpful.

I had double incision top surgery which involves removal of mammary glands, and I had nipple grafts which severed the milk ducts – this kind of top surgery makes it the most likely you will produce no milk. There is a small chance you will produce some, as the mammary glands extend all the way to the armpits where the top surgeon probably didn’t remove tissue. In the event that your nipples heal as well as mine did, some of those ducts can reconnect and you may produce a very small quantity of milk. This was the case for me, leading to a little puffiness at the sides of my chest, though the shape is not beyond what a cis man of my size might reasonably have in the way of chest fat. Left alone, milk production stops fast and swelling reduces within weeks. I let my baby chestfeed a few times to soothe her and seek the immune benefits, however production is minimal (a few mls per time) and isn’t worth accounting for with regards to how much she’s bottle-fed.

Someone who had a different type of top surgery which removes fat but keeps the nipples intact and avoids removing the mammary glands, such as periareolar aimed at preserving sensation and function, may be able to chestfeed to a greater extent. You still should not rely on your milk supply being enough to provide everything a baby needs, so you should be prepared to use formula for the majority of their nutrition, but the possibility is higher that a significant portion of their feeding could come from milk from their parent.

Be aware that regardless of surgery type, or if you haven’t had any, the more milk you produce the larger your chest will get. It will be made larger by milk and hormonal swelling, so this should go away once you stop feeding your baby via this method, however the skin may remain stretched somewhat. For double incision, the swelling will be localized to the area where tissue wasn’t removed or less was, such as just under the armpits.

It is a good idea to practice before giving birth with a pump, testing how to grip the skin and flesh to create enough of a mass for a baby to latch onto. Babies do not latch onto the nipple itself, but the tissue around it. You may have to manipulate your chest and hold the skin together for the baby initially. Once medical staff understand how low your supply will be, they may discourage you from trying, but stand firm if it’s something you want to do – any amount of milk can have benefits for your baby’s immune system.

In a scenario where you have not had top surgery, or have had a kind of top surgery which does not entirely preclude you from chestfeeding to some degree, you may also come across misinformation from midwives and doctors about the safety of doing so while on testosterone. It is perfectly safe for a baby to feed from someone who is on testosterone and it does not transfer to the child (just be careful if you’re on get that you’re not applying it close enough to the area that baby comes into contact with it while wet), with the only concern related to HRT being that you should wait 4 – 6 weeks for milk supply to be established if you don’t want to risk losing it and lowering production! Chestfeeding should not delay you returning to being on testosterone or starting it for the first time.

Get an appointment with an endocrinologist or other specialist in trans care if you are able to. Their word will be taken more seriously than your own, so having a letter confirming what you are telling midwives and doctors about your needs can help you to gain their support more quickly.

What to do if something goes wrong?

Familiarize yourself with the complaints process in advance. Make a list of any phone numbers you might need to complain about treatment at a pre-natal appointment, the hospital or birth centre where you give birth if you aren’t doing so at home, or your family doctor/GP. In case the worst should happen, also get yourself the number of a lawyer who can offer you advice and vet them in advance to be sure they are not transphobic.

Good luck on accessing the antenatal care you deserve!

Remember that you can always reach out to friends, advocacy services, and other trans people who’ve been through pregnancy whether we know you personally or not. There are plenty of us who are willing to help you through what is likely to be a difficult time. My baby is worth every bit of struggle through pregnancy and birth, but I absolutely wish I’d advocated for myself harder and had more information about certain things earlier. If you’re a trans person interested in getting pregnant and have more questions, don’t hesitate to contact me on any of my social media @mxjackparker or drop me an e-mail or comment here!