The National Police Chiefs’ Council has created sex work guidance e-book for the UK which is due to be reviewed via consultation starting on the 1st of April 2024 and to be finalized and issued by the 1st of August 2025.

This is a breakdown of the current guidance, including criticisms from a sex worker perspective.

Principles

Principle 1 – “The sex industry is complex, often stigmatised, and has many evolving typologies. It is often hidden from the wider public. We recognise this environment is conducive to the abuse or exploitation of those selling sex.”

This principle is a reasonable one, noting that stigma encourages the abuse and exploitation of sex workers and committing to recognizing that.

Principle 2 – “We will engage with sex workers to build mutual trust and confidence and encourage the sharing of information to improve safety. Our role does not include making judgements about personal morality.”

The latter part of this principle is good and could reasonably be a principle all on its own – police officers often make judgemental comments towards sex workers and could do with being discouraged from arguing that our behaviour is immoral.

Unfortunately, the focus of this principle is on encouraging sex workers to share information, supposedly to improve our safety. In reality, rather than the fantasy world this principle seems to be based on, giving information to the police actually puts sex workers into more danger. Engaging with sex workers to build trust, rather than letting us decide whether we want to engage with police, is a failure to consider our preferences and to treat us as anything besides victims that they infantilize. Respect towards sex workers would lead police to leave sex workers alone unless their presence is directly requested by sex workers ourselves (which it generally will not be, due to a long history of harassment and mistreatment and criminalization).

Principle 3 – “We will start from a position that seeks to tackle exploitation, encouraging the reporting of crimes against sex workers and taking enforcement action against criminal perpetrators.”

Rather than starting from a position that seeks to tackle exploitation, this would be better phrased as starting from a position that seeks to support sex workers who are exploited. Considering that the police often decide sex workers are exploited merely because we work in managed premises or because we use drugs, a position of always tackling this supposed exploitation rather than respecting what we want and need is not necessarily ideal.

Additionally, because current laws around sex workers are deeply flawed, enforcement against “criminal perpetrators” can often include sex workers ourselves who have done no harm but have broken the law in the process of trying to work more safely. These laws include, and are not limited to: brothel-keeping (working from the same space as another worker), causing or inciting or controlling prostitution for gain (renting rooms to other sex workers, earning money for referring another sex worker to a brothel, being paid to help another sex worker with their advertising).

Principle 4 – “We will seek to maximise safety and reduce vulnerability. We will work with partners to develop a problem-solving approach that tackles issues these issues.”

Depending on who these partners are, it’s promising!

Principle 5 – “An evidence-based ‘what works’ approach will be used to enhance awareness of officers and partners dealing with this complex environment. It will ensure the focus is on vulnerability and safety and a consistent approach across the country.”

Current enforcement is variable across the country, with some police officers being much stricter than others, so consistency could be a positive thing assuming that the police are consistently hands-off and actually consider the wants and needs of sex workers.

A ‘what works’ approach leaves us wondering what the goal is, to consider something to be working. A focus on making sex workers safe would be good, but as we’ve seen from principle 3 there is also an emphasis on arresting criminal perpetrators. Sometimes arresting those that the law considers to be perpetrators will cause harm to sex workers, either by criminalizing sex workers ourselves or by arresting our bosses and cutting off our income. If something ‘working’ is assessed based on the number of arrests, or even the number of reports of violence from sex workers who rarely report to the police, this sort of approach may not actually be beneficial.

Terminology

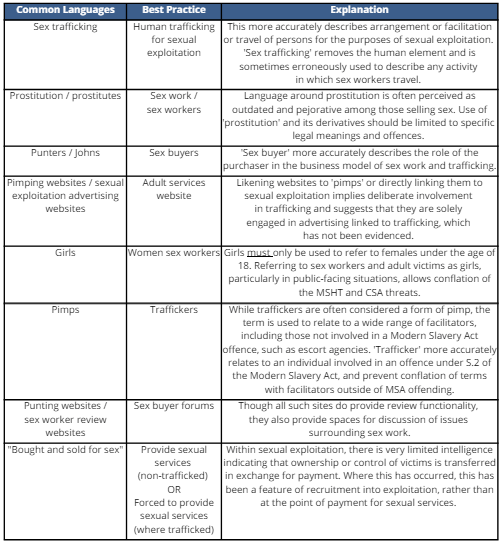

The report goes through many different terms, giving a list of the common words or phrases used around the topic of sex work and the words or phrases they recommend as best practice instead.

The term sex trafficking being substituted for human trafficking for sexual exploitation avoids being dehumanizing, which is a positive feature of the shift in language. However, one of the criticisms given of the term “sex trafficking” will also apply to the new terminology; this phrase will still be used to label any activity where sex workers travel, because the law itself in the UK is often interpreted that way.

“You commit a human trafficking offence if you arrange or facilitate the travel of another person (“V”) with a view to (V) being exploited. It is irrelevant if (V) consents to travel.” (MODERN SLAVERY ACT, 2015, S 2(1).)

There are certain groups in the UK who view buying sex from someone, in itself, as exploitation. Though the law is more strict in its definition than this, it is still the case that anyone who makes money from another person selling sex and who facilitates their travel is considered a trafficker even when they consent. The new phrasing is less dehumanizing but does not fix this issue!

Calling clients sex buyers is not incorrect, and for the purpose of reports it can be useful for clarity, however the term client is notably not mentioned at all and I find that strange. The term client is used in a variety of industries, yet this guidance opts to call clients “purchasers” even in the segment giving the reasoning for the word choice. It reads like they object to viewing the transaction as the sale of a service, as they would in other industries.

Despite this recommendation, the guidance itself uses the word “client” 8 times and uses the phrase “sex buyer” only 5 times (2 of which are in the terminology section recommending the term). This is likely because the groups they consulted with to create this guidance used the term client, which is preferred by sex workers, so much that it ultimately made its way into the document.

On the matter of using the term “girls” to refer to adult women who sell sex, this sort of language is often used by police to infantilize and demean sex workers whilst minimizing our abilities to make our own choices. For this reason, I’m pleased to see the problem acknowledged.

The Nature of Sex Work

“Clearly, some people are subject to activities by third parties, which makes them victims. This can be as obvious as being forced or coerced into providing sexual services or having their activities controlled. Rape and other serious offences can be inflicted over sustained periods of time causing significant and lasting harm. People who do not consent to the activity they engage in are not to be considered sex workers. They are victims or survivors of sexual exploitation. People who do consent to sexual activity but are subject to control may not be able to give true consent.“

This paragraph on the nature of sex work fails at understanding victimization and harm from its very first sentence. The idea that any sex worker who is subject to “activities” by third parties is a victim is deeply unreasonable. Working in a brothel where you give a percentage of your income to an employer, with rules about when and how you can work, is not fundamentally different from other jobs where a person has an employer and rules about when and how they must work to be paid. If the police do not consider the average worker who has an employer to be a victim, then framing sex workers this way is not consistent.

Since the current law criminalizes third parties, this phrasing seems to exist to frame sex workers as victims in all cases where third parties are involved to excuse this law.

In cases where people who are selling sex are coerced, they may or may not consider themselves to be sex workers depending on circumstances, as is the case with people forced to engage in a variety of types of work. Whilst police should take care not to label people, especially rape victims who have been forced to sell sexual services, they should aim to use the language that people want used for themselves.

When referring to other forms of exploitation involving payment for services or time spend making products, we still use terms around work and labour (e.g. child labour, sweatshop workers), so calling someone a “sex worker” is not incompatible with speaking about them as a victim of exploitation. There are exploited workers in a variety of industries.

The guidance then breaks down people who sell sex into categories. I find this to be a bizarre categorisation system.

For some reason, despite using the terms “sex workers” and “sex entrepreneurs”, the phrase “survival sex” has been used for “those who engage in commercial sex because they see no alternative”. Survival sex… what? Survival sex is a thing people do, not something they are. A person who sell sexual services out of desperation is not a “survival sex”, they are a survival sex worker. I can imagine that the word “worker” was avoided out of a desire not to label people who are likely to be coerced or who do not want to be selling sex, however without an alternative noun this category doesn’t make sense. “Person engaging in survival sex” would at least be consistent with the previous stated desire not to dehumanize.

The definition given is also not ideal, as it relies on knowing the inner beliefs of the sex worker and doesn’t refer to circumstances. A survival sex worker is usually a person who sells sex to meet their immediate needs, such as shelter or food or drugs, often trading sex directly for these things. Whether someone sees an alternative or not isn’t actually relevant, because many people in this situation do see alternatives but determine that selling sex is the best of the options available to them. The definition given in this guidance minimizes the choices made by survival sex workers.

The guidance acknowledges a much more accurate definition of survival sex work on the next page, “In short, the definition could be seen as ‘selling or exchanging sex for food, shelter, drugs, to pay bills or safety’.”

The guidance then separates out “sex workers” and “sex entrepreneurs” in a way that simply seems to denote class. If someone decides to sell sex because they think they would enjoy it, with plentiful other career options and wealth, they are considered to be an entrepreneur, but if a working class person chooses to sell sex as an alternative to minimum wage jobs they’d like even less, they do not obtain this label. I would personally advise that the “entrepreneur” category be dropped altogether, in favour of simply acknowledging that some sex workers have more money and options than others.

Survival sex workers are also not necessarily the group that police are most likely to encounter, but they are the group that the police are the most likely to subject to surveillance and raids and seek to speak to about the topic of sex work.

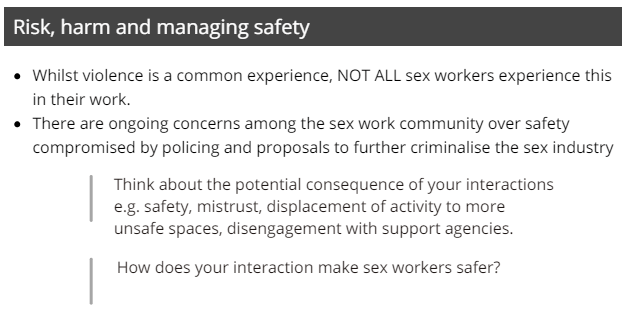

When it comes to the risk and harm sex workers face due to policing, it is useful that police officers are being encouraged to think about the potential consequences of their actions. They also need to be enabled to refuse to act, when the consequences will be negative and compromise sex worker safety.

If it is expected that police officers will ask themselves “how does your interaction make sex workers safer?” and that they will not act if the interaction does not make sex workers safer, then the National Police Chiefs’ Council should be prepared for officers to have far less interactions with sex workers. As there is no mention of intentionally lowering the number of interactions, it seems like an assumption is being made that most of the times that police meet with sex workers are helpful and only a handful are the negative experiences colouring the opinions of the community.

Wider Forms of Online Sex Work

Instead of separating online sex work (porn, phone sex, etc) and online advertising, both matters are discussed in the same segment of this guidance. Using language this way makes it less intuitive for sex workers who intend to read this guidance for ourselves to have an understanding of the ways we are likely to be policed, and also makes those in law enforcement used to using terms like “online sex work” to refer to advertising online in a way that would be confusing to any sex worker they speak with.

With regards to targeting sex workers for safeguarding visits, which sex workers at best tend to find irritating and at worst are traumatized by, this guidance suggests taking the data that these websites have about sex workers who are desperately trying to remain anonymous and requesting it so that they can conduct “safeguarding visits”.

“It is good practice for police forces to scan ASWs for vulnerability and signs of exploitation before conducting safeguarding visits.”

Being a vulnerable person is not a crime, yet in the case of selling sex it seems to be a reason to subject sex workers to more police presence. With the data available to the police from adverts, it is much easier to find out someone’s real name and location than it is to find out whether or not they are being exploited. The guidance to seek out this data, when it will expose the identities of sex workers and very rarely yield anything useful even in cases of exploitation, is a frustrating recommendation when sex workers are seeking to remain anonymous as best they can.

Professional Standards

“The use of sex workers is now incompatible with the role of a police officer or police

staff member.”

This is the first line of the professional standards segment, referring to sex workers as if we are objects that are used. The phrasing that this guidance should opt for when discussing this expectation is that police officers should not pay for sexual services. Sex workers are people paid for services, not things that people pay to use. For a document which has earlier mentions of the need not to dehumanize sex workers, this is a shockingly bad misstep.

After this expectation is established, the reason for this follows:

“When police officers or staff make use of services offered by sex workers there is an

obvious significant risk that this is highly likely to undermine public trust. For that

reason, police officers and staff should not procure or attempt to procure physically

provided commercial sexual services or other services. To do so would compromise

their professional position.”

The primary reason police officers should not hire sex worker or pay for sexual services is not simply because it is likely to undermine public trust (the reason why this would do so is not even given), but because police officers have significant power over sex workers as a population that are subject to high amounts of criminalization around our activities. When police officers pay sex workers for sex, this power dynamic can frighten sex workers as well as make us feel less able to refuse their desires as clients out of concern for how they might use the law to do us harm. They also should not do so for the risk that they will run into the same sex workers they have paid in the course of their work.

An additional and extremely interesting point that is made is that if police officers do hire sex workers, “It is very unlikely that an officer or staff member would be

able to adequately assess the vulnerability or welfare of the sex worker, including the

identification of human trafficking/CSE indicators. This may in turn lead to criminal

allegations under S.53A of the Sexual Offences Act.” Apparently assessing their vulnerability or welfare is very unlikely to be possible, and yet the police conduct welfare checks on sex workers which give them access to that same amount of information and see these as worthwhile.

Harm Reduction Compass

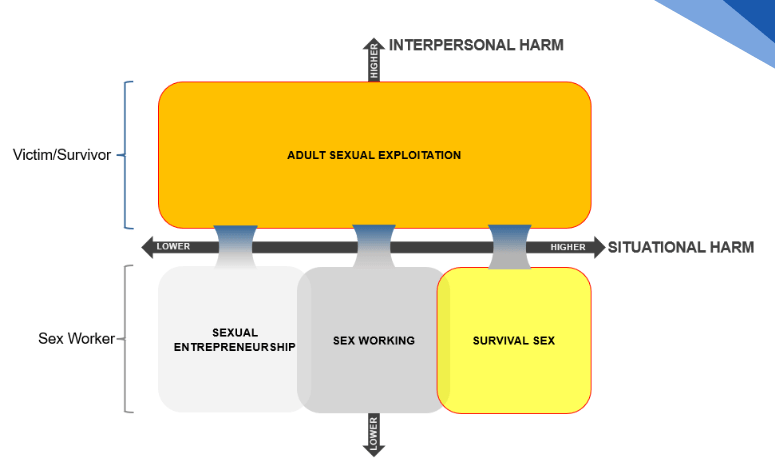

The guidance discusses harm reduction and how the police should prioritize adult sexual exploitation which is likely to have high interpersonal harm, over sex work which may have low or high situational harm but generally has lower interpersonal harm.

This diagram has many issues. It uses “sex worker” as an umbrella term, correctly, but because “sex worker” has been chosen as a term to describe working class people who sell sex whilst having limited options, the diagram uses the term “sex worker” to be a specific type of sex worker. Understandably, this will confuse people, because “sexual entrepreneurs” and “survival sex” are being considered types of sex worker at the same time as they are labelled as distinct from sex workers.

Additionally, those who engage in survival sex are spoken about as a group who feel they have no choice but to sell sex, and yet according to this diagram they experience “low interpersonal harm”. The funnels between the groups are useless when the diagram itself tries to create a distinction between interpersonal and situational harm that does not exist. Those who experience a large amount of harm due to their situation, like the negative impacts of poverty, will also be vulnerable to much more interpersonal harm.

Hate Crime Approach to Crimes Against Sex Workers

Approaching crimes against sex workers as hate crimes, similarly to making sex workers an inclusion health group, has positive effects for sex workers who end up engaging with the legal system compared to a scenario in which we report crimes and they are not treated as hate crimes. It would, however, be erroneous to suggest that an improvement means that the outcomes are good overall. Sex workers are likely to face stigma for reporting, will be known to the police as sex workers, and many are aware of this and opt not to report for these reasons.

Guidance for Community Problem Solvers

With referrals being given to services that are not within the police, sex workers are better able to be supported without the threat of criminalization. Understanding what these services do and recommending that sex workers access them, rather than the police getting involved in all issues that sex workers have, is a useful recommendation within this guidance.

Guidance for Front Line Police Officers

Safeguard the Vulnerable

Officers are instructed not to “criminalise sex workers simply for being sex workers or for engaging in practices that have been undertaken to increase their own personal safety”, and as part of this are told to “ensure individuals in brothels know that if they are only providing sexual services and are not involved in the management of the brothel, they are not committing an offence”. The expectation that those who manage brothels are criminalized is not fully compatible with a recommendation not to criminalize sex workers for the safety precautions they take. Many sex workers end up involved in the management of a brothel to increase their own personal safety. Two sex workers selling sex from the same premises are considered to have created a brothel, so if they do so to be safer than working alone then one or both would be breaking this law. Of course sex workers should be informed of the law, so they can avoid telling members of law enforcement anything that might get them arrested, but the enforcement of that particular law does lower sex worker safety.

Focus on Exploitation

Several of the suggestions here about how to assess for exploitation are accurate and somewhat refreshing to see: the understanding that not all exploiters are male, the instruction to assess sex workers individually rather than treating us as indistinct members of a collective, and an awareness that sex workers being seen speaking to police may have negative consequences for them.

When it comes to the indicators that coercion and exploitation are occurring, the list of them has some major flaws. Only some of the indicators include clarifications about reasons that someone may exhibit these behaviours that are not exploitation or coercion. Here is a run-through of the indicators given:

The inability to edit their escorting adverts – The guidance admits that this may be due to language barriers rather than exploitation, and suggests that officers consider the possibility that the sex worker (or sexually exploited person) does not have a say in what their advert says or what services they offer. A third party is going to be involved if someone else is editing their escorting adverts, but that person could be a friend helping with translation or a controlling partner or a variety of other person.

Not controlling their own contact number – Similar to the inability to edit their escorting adverts, this means another person is involved. This person might be a friend or personal assistant, again because of a language barrier or simply a lack of desire to answer the calls or texts directly. Police should not automatically assume this means exploitation either.

High risk services on offer – No clarification or caveats are offered for this indicator, and this should be expanded on. Plenty of people have casual sex without using protection and this is not automatically seen as evidence of abuse, so it should not be seen that way among sex workers either. Whilst using protection with sexual partners should be encouraged, someone choosing not to use it is not in itself evidence they are being controlled or harmed. People are more likely to offer high risk services when they have a greater need for money or business is slow, and as previously discussed in this guidance the priority for police is supposedly high interpersonal harm and exploitation and not the situational harms that come with poverty.

General working conditions – Working conditions may be poor because of poverty as well as because of exploitation, and these possible causes should be differentiated so that poor people are not disproportionately targeted for police intervention that is potentially traumatizing in a classist manner.

How the sex worker screens clients – Screening methods vary by area, number of clients, preferences of the sex worker, amount of time available to screen, living situation (not wanting to be overheard on the phone by people they may live with), and whether a sex worker is using screening applications on their device. Simply whether sex workers tend to arrange to see clients over text or call or webcam does not provide the police with information about whether they are exploited.

The individual cannot explain where their money goes – The guidance recognizes that sex workers are likely not to want to tell the police this, but speculates that those who are exploited may be afraid to reveal that a third party is taking their money. Both these possibilities being included is helpful, because a significant number of sex workers will fall into the first category and should not be assumed to be coerced on this basis.

Once the police have a suspicion that exploitation is happening, they are encouraged by the guidance to gather intelligence and offer support. It is suggested that the views of the sex worker the police are engaging with, as well as their vulnerability, are taken into account when deciding whether to investigate or how much.

“Some sex workers work for, or have their business organised by, third parties such as agencies. This practice may fall into the S.53 offence, so in these circumstances the views and vulnerability of the sex worker should be a significant factor when considering the extent of any investigation. The collection of intelligence should still occur.”

It would be useful if the guidance were to clarify to what extent the sex worker’s views and vulnerability should be taken into account by officers and what sort of views are being referenced. For example, if a sex worker is highly vulnerable but is very happy working for their agency and would be thrown into severe poverty if they were unable to work through that agency anymore, is this sufficient for the police to choose not to investigate or arrest the people who run the agency? Does the vulnerability of the sex worker override their desire to keep working for their agency and not see it shut down? The best outcome in that scenario, for the sex worker to continue being happy and stay out of poverty, appears to be that the police disengage. Would they do so?

Build Trust and Confidence

This segment starts out strong with specifying that offences against sex workers are not “an occupational hazard”. Sex workers are often told by police and the general public that we should expect to be assaulted due to our profession, as a form of victim-blaming, so this clarification is very beneficial.

Something I am very pleased to see in this section is the statement “often the worst time to engage with a sex worker is when they are working”. This is absolutely true, because obviously someone will react negatively if you interrupt their work day and cause them to lose out on money, particularly if it is money they desperately need. Sex workers also frequently get into a specific mindset and rhythm for work and may be working in a criminalized environment, so all of these factors will mean they are caused greater discomfort by police intervention.

Avoidance of recording sex workers is vital, as many take great pains to remain anonymous. Not turning on police body cameras is recommended in the guidance, so that no images of the workers are captured, and this is a matter of basic respect to protect their anonymity. This is undercut, however, in cases where the police have already obtained their verification pictures and real name from escorting advertisements online, so the avoidance of collecting personal data and images of sex workers should be made more consistent. It is also important not to record sex workers in compromising positions or states of undress, as they may be found if police are entering their workplaces.

Guidance for Reactive Investigations

The order provided in the report for what officers should do during investigation is flawed. Understanding vulnerability should come first, followed by supporting any victims as the first priority. The suggestion that once the vulnerability of potential victims is understood, the next step should be to target exploiters, undermines the earlier statements guidance suggesting that the situation of the individual and their desires should be taken into account.

Offences against sex workers may have a higher concentration of types of harm that are less common among other members of the public, such as doxing and stealthing, so the mention of these offences in the guidance is helpful as a prompt for officers to inform themselves about these.

Again, it is suggested that the vulnerability of sex workers should be taken into account when deciding how to investigate or pursue charges against third parties, “Some practices by sex workers may suggest exploitation or organised criminality, but, equally, they may be used for personal safety reasons (for example the use of drivers or working for an agency).” The guidance should directly state when it is encouraged for officers not to pursue third parties for criminal charges, rather than only implying it.

Partnership Working

It is rightfully noted in this guidance that non-police organisations that exist to support sex workers will have much more direct contact with us and will have experience working with us holistically.

NUM is a specific partner that is discussed the most extensively within the guidance, and is a group with great resources for sex workers who they can be referred to. It would be worthwhile to explicitly suggest that officers familiarize themselves with NUM, including the understanding that NUM takes the position that sex workers should never be pushed to engage with police when they do not want to.

Guidance for Scanning Vulnerability

It can be difficult to tell the difference between a person who has put up an advertisement for themselves on an ASW (adult services website), which this segment of the guidance recognises.

“As ASWs are the largest marketplace for sexual services, they are also exploited by traffickers and organised criminals who seek to make profit from the exploitation of vulnerable victims by advertising people online and making the profiles appear to be voluntary sex workers.”

This mention of the difficulty telling between those who are forced to sell sexual services (victims of adult sexual exploitation) and those who choose to sell sexual services (sex workers) fails to use the terminology outlined earlier in the document, as yet another example of inconsistent language being used. Based on the way that the terms were defined earlier, the term sex work is supposedly only being used in this document to refer to the voluntary sale of sexual services, so the word “voluntary” is redundant and it implies the existence of “involuntary” sex workers.

The guidance also accurately recognizes that it is difficult to tell whether someone is being exploited only by an advertisement.

“It should be remembered that the vast majority of services advertised on ASWs are by independent sex workers and these should not be the focus of police activity. However, given the difficulty in distinguishing between independently advertised services and those which have been coerced or controlled, it is likely that there will be engagement with those who are not being exploited. Where this happens, the focus must be on building trust and increasing safety, which may involve signposting individuals to support agencies and local sexual health provisions for example.”

It should be recommended that when the police engage with sex workers who are not exploited, having done so out of concern that they are, that sex workers should be allowed to immediately disengage with the police and that this decision should be respected. With the way this suggestion is currently phrased, it implies that officers are expected to jump directly from seeking evidence of exploitation to using sex workers as sources for information without concern for the fact they are likely not to want to be bothered.

The negative impacts of this kind of engagement with sex workers who are not being exploited is noted, with “excessive scanning and proactive engagement can lead to unwanted interaction with non-vulnerable sex workers and erode trust.” However, this guidance fails to note why this would erode trust and how it will bother sex workers for police to show up unrequested.

On Street Sex Workers

Outside of the exploitation which harms sex workers, this segment mentions that police may need to respond to the “needs of residents and others affected by street sex working” but does not specify what those needs may be. Residents in areas with street sex working may make complaints because of stigma against sex workers, disliking that they see them in the area, and this is not an adequate reason for police intervention. What kinds of “needs” are seen as meriting a response from the police should be specified.

When there is engagement with street sex workers, with regards to the offences the sex workers commit, this is the recommendation given:

“Where officers suspect and/or have evidence of loitering, offences should still be recorded and evidence retained, however, it will not be commonplace to seek to prosecute those who sell sex. Instead, every effort should be made to refer these individuals to partner agencies and seek a diversionary route wherever possible.”

Saying that prosecutions will not be “commonplace” does not provide sufficient information about when prosecutions may be sought, or why it would be in the public interest to seek them. Coupled with the mentions of partner agencies and diversionary routes, the implication seems to be that if individuals reject police intervention and do not want to seek support from other services, they may be punished for this through prosecution even when that is in no-one’s best interest. It should be stated whether or not these sex workers will be penalized for not desiring to engage with these partner agencies.

It should also be noted that knowing it is possible they will be prosecuted for loitering or soliciting, even if it is common, will prevent sex workers from being willing to engage with police or disclose having been assaulted or exploited. A firm line that sex workers will not be prosecuted for loitering or soliciting at all would resolve this.

Brothels

“Despite the legal standing of brothels, the priority should be to penalise those who organise the selling of sex and make a living from the earnings.” This position helps to avoid sex workers being prosecuted when they form a collective, and though brothels are treated as problematic, “sex workers gathering together at the same premises for safety should not mean they are criminalized under brothel keeping legislation” according to the guidance.

A problem lies with the fact that sex workers often gather together for safety in premises that are managed by third party, because they do not have the financial capital to rent their own premises alone. In this case, criminalizing the third party does still put those sex workers at risk, cutting off their income and leading to them selling sex in more dangerous circumstances once the brothel is closed. The assumption seems to be made that brothels are inherently dangerous or unacceptably exploitative for sex workers to work in, which is not substantiated.

The recommendation is made that “if a location is being used as a brothel and is the cause of anti-social behaviour, there may be less intrusive ways to tackle this type of complaint. Interacting sensitively with the occupants may immediately address community concerns.” Avoiding entering brothels unannounced means that sex workers will be much less defensive or upset, that the police will not cut off their ability to work and earn money, and that workers will be less frightened by interactions with them. Less intrusive ways of tackling the complaint are idea, though some quick examples being added here would be ideal.

Advising that warrants on brothels are not used to criminalize sex workers is also an important part of this guidance, which will allow sex workers to be less fearful of raids.

Evidence from brothels

The first listed piece of evidence from outside of a property, of bins containing used condoms and wipes, should be removed. This being used as evidence that somewhere is a brothel can mean sex workers are discouraged from using condoms, as the presence of them will be used against them, so this way of assessing whether somewhere is a brothel will encourage unsafe sex practices.

Male Sex Work

The claim that “public attitudes towards MSW and FSW are markedly different with less stigma, judgment, negative language and prejudice shown towards MSW” is made within the section about male sex work in this guidance, completely unsubstantiated, immediately after commentary about inaccurate assumptions being made about the sexuality of male sex workers. Male sex workers are subject to homophobia and the stigma they experience for selling sex is strongly related to it, with people holding beliefs that gay men are inherently very sexual and deviant and that their engagement in sex work is due to a low level of sexual morality related to their queerness. People do not have more positive attitudes towards male sex workers who sell sex to men than they do towards women who sell sex to men.

There are more women who sell sex than men, so people think of women when they think of sex workers unless otherwise specified, which means a lot of the prejudice around sex work as a whole is launched at women in particular. This does not mean that men selling sex do not face the same levels of prejudice when they are known to do so.

The guidance does this itself, assuming that sex workers are women except for in the section about male sex workers who are repeatedly called MSW rather than simply “sex workers”, despite the fact that women who sell sex are not called FSW except for in this segment. This idea that sex workers are women as the default means that men selling sex are afforded less consideration and are therefore failed by services which are not built with them in mind.

Male sex work is only given one page in this guidance, and since the rest of the guidance generally assumes that sex workers are women this means the document ends up contributing to the problem it highlights, that they are overlooked.

Migration

Background on the diverse experiences of migrant sex workers is useful for police to have, so that they do not have a stereotype of migrant sex workers in mind and act based on that. Not all migrant sex workers are victims of trafficking and the guidance would benefit from stating this more clearly. As it is currently phrased, it is implied that migrant sex workers are generally victims of trafficking but do not always recognize themselves as such, rather than acknowledging that some immigrants will take up selling sex as a job in the same way an immigrant might begin doing any number of other jobs.

Focusing on the cases where there is significant exploitation and migrant workers are coerced into selling sex by third parties, the guidance acknowledges that fears of deportation are a large barrier to reporting:

“For law enforcement to be able support the most vulnerable migrant sex workers, it is paramount that there is – and that they know that there is – a clear separation between immigration law enforcement and sex work law enforcement. That migrants know that they do not risk deportation if they need protection from the police. Unless this happens, law enforcement will be seen as a threat and not as an opportunity for migrants, even when they experience exploitation and trafficking.”

Raids of brothels have been known to change into immigration raids, in cases where sex workers do not disclose the actions of third parties and appear to be migrants, so an end to this practice would significantly lessen the fears that sex workers have around disclosing harms done to them if they are immigrants.

Reference Documents

Examples are provided of the experiences of sex workers when engaging with the police at the end of the document, though they are limited in scope and involve sex workers who have been referred to the police through NUM and with their support. It would be useful for examples to be provided, anonymized, of sex workers that the police have engaged with through direct reporting, particularly because this helps to demonstrate how the involvement of groups like NUM is beneficial and what should be done when a sex worker who is reporting something has not engaged with other groups already.

The key legislation is also listed, which is useful, however there are earlier points where a condensed description of the legislation and potential penalties would be useful. Adding in the penalties in the cases that the police may choose to penalize sex workers would help to give context, such as a mention of the size of fines which might be used against street sex workers who are already usually in significant poverty which causes them to sell sex in the first place.

This concludes my breakdown of the National Police Chiefs’ Council Sex Working Guidance!

While this guidance was created in conjunction with many groups, there are basic inconsistencies within it in terms of language and recommendations, potentially because of the different terminology used by each.

This document will be reviewed between April 2024 and August 2025, and I hope that the issues I have outlined and the questions posed will be resolved by then.

Thank you for reading!