Disclaimer: This article will cover the TV show Interview with the Vampire seasons 1 and 2. Though I will briefly reference the original books it was based on when they provide context for something only alluded to in the show, the commentary in this article is limited to the TV show.

Interview with the Vampire (2022) is not a show that is explicitly about sex work, and yet selling and trading sex is a vital aspect of many characters and has a core importance to the story.

The first reference to sex work that we hear is from Louis, who uses a euphemism and calls managing the sale of sex “a righteous business” when he introduces his past profession as a pimp back in 1910. With a barely a prod, he skips to calling sex work “gluttonous whoring”, but still cloaks it in vague language when he speaks of his involvement in running brothels no matter how direct Daniel’s questions get while interviewing him. This sets a tone for how we are expected to view the sex work we are shown, through Daniel’s eyes rather than Louis’, even when the scenes are narrated and shown from Louis’ memory.

Once we meet the first sex worker to be shown, an incredibly minor character with only a couple of speaking lines, it is made clear in a matter of seconds that the show intends to humanize the sex worker characters and treat them with at least some level of respect. We are told Doris’ name as the second word out of our protagonist’s mouth, she has a disability that is not mocked, and she walks outside wearing period-appropriate clothing that would be expected on a woman working in a brothel.

We’re given a peek into the lives of the sex workers that Louis managed before we hear the way the rich white men who own various other brothels speak about them. Our introduction to their world includes the aftermath of an assault where a sex worker is framed as being in the right for violently defending herself. The work is by no means glamorized, but it is also not treated as some sort of unique horror into the context of the intersection of racism and sexism and poverty that the women we see would have been subjected to at the time. Other workers gather around the scene and even giggle over the comments one of them makes, which was deeply relatable to me as someone who has worked in brothels. They accurately showed the sort of camaraderie that forms in those environments.

Upon my first watch of Interview with the Vampire, I was pleasantly surprised by the first 45 minutes or so because of the accuracy and relatability. It’s rare that I see sex worker characters treated with such care, where the narrative itself does not degrade them. I became enamoured with Lily, a sex worker that Louis pays to see and mostly talk with, and how she’s shown to de-escalate conflict between Lestat and Louis as they interact with hostility at first. We don’t see much behind the mask of her work persona, but her open-mindedness about queer relationships is demonstrated when she reacts with encouragement to interactions between the two men who’ve hired her for the night. I could see women I’ve known in her, catering to wealthy clients and keeping their secrets.

Lestat is shown to be the sort of man to pay for sex, as an extension of his willingness to pay large sums for all sorts of extravagances. He is a client to sex workers because he is a hedonistic man with a willingness to spend money to indulge. At the point when he becomes fixated on Louis, this indulgence turns into a way to fuck Louis by proxy. He fixates on Lily because Louis sees her as someone it would be acceptable for him to be attracted to, and thus Lestat showers her with public affection and goes so far as to have a carriage ordered to bring her from the brothel to his home. This would not work if Lily were not charging for her services, because it would imply a closer level of intimacy with her which would spark jealousy. Her status as a sex worker allows her to function as a surrogate for Lestat and Louis’ true desires.

As I reached the end of that first episode and Lily was killed off-screen, provoking a self-flagellating speech from Louis to a priest where he acknowledged the way he profited from disadvantaged young women by acting as a pimp, it complicated my initially very positive feelings. I didn’t want to see another grisly scene of a sex worker being murdered like I’ve seen in so much other media, but I also couldn’t stand to see her killed off with quick justifications from Lestat before she was forgotten. I wondered at that moment whether my angst over it was fair, in a show where so many characters are killed off. With so many sex workers woven into the narrative, of course at least one would die. It stung me more because it made me recall sex workers in my own community who have been killed.

If you, like me, hesitated at this point… keep watching.

One of the things that makes the show so interesting is the way it plays with memory and unreliable narration. Louis acts angry about Lily’s death for a split-second of screen time and moves on, but the audience has the tools to read between the lines because we’ve seen his admission of the harm he’s done to the sex workers he controls. When he convinces Lestat to help him buy a far more expensive and up-market brothel, his present-day self narrating how he improved so many lives at the same time that he speaks about how rich he became, we can see how little he truly cared for Lily. His callousness about her death isn’t the show disregarding the worth of her character, it’s Louis doing so. My reservations about the show lessened the more I watched.

Since the brothels are such an integral part of the early story, Lily’s death doesn’t remove the only sex worker presence from the narrative. The logistics of fighting city ordinances that lead to brothel closures are the backdrop to Louis and Lestat having relationship troubles. Bricks, another named sex worker who we saw defending herself from an assault at the very start of the show, is shown to be a competent businesswoman who can hold her own in discussions with powerful men who would seek to degrade her. These choices appear to have been made to make engaging with these characters unavoidable.

I found it incredibly compelling that while Louis struggles against the racism of white men who are far wealthier than him, we see both his justifiable rage and his callousness towards the (majority black) women he has hired to sell sex in his establishments. Every time I watched him make a choice to react to the racist mistreatment he suffered in a way that caused a backlash against those sex workers, I felt like it made sense for his character and highlighted the way that racism and whorephobia and misogyny all interact. That’s the kind of commentary I expect out of a book on sex worker history, not a work of fiction.

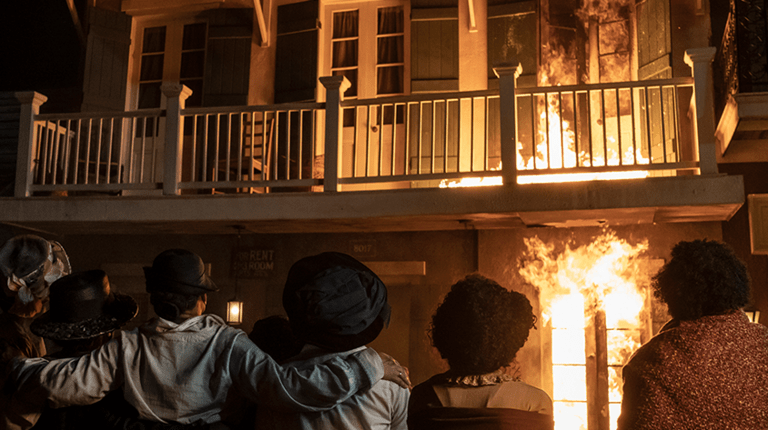

Unfortunately, as soon as the district where all the brothels are is destroyed, there’s no follow up with any of the sex workers who presumably survived. Louis doesn’t care once they aren’t making him money, so he doesn’t seek them out, and he’s the audience’s eyes.

If the sex work were limited to this one storyline, I wouldn’t be discontent but I also wouldn’t be particularly impressed. These characters ultimately exist to serve Louis’ character development as an exploiter, his pimping used as an alternative slave ownership within the books. Thankfully, the show continues to develop on these themes.

Through flashbacks to Daniel’s first interview of Louis in the 70s and exposition from Armand, we gradually see how selling and trading sex has impacted the perspectives of our main characters as well as background ones. This changes not only how we see Daniel and Armand but also how we see Louis.

The language Louis uses in his memories is consistent with what I would expect. He calls the sex workers he manages his “girls”, “whores”, “hookers” and plenty of other names that are derogatory or euphemistic to various degrees. These words faded into the background until I no longer noticed them. My attention was sharply called back towards the terminology used when in season 2 Armand finally said “sex workers” whilst describing the unseen people who lived in Louis’ apartment complex.

Period-accurate terminology makes sense on the context of Louis’ memories of the past, but in the present day there’s no reason he has to use those same words. In his narration, he hides behind the attitudes of the early 20th century to obscure how similar the issues sex workers faced at the time could be to the issues sex workers face now. Once Louis is no longer involved in exploiting them, they get to be “sex workers” who make Louis more sympathetic through his proximity to them. Suddenly his status has been lowered to mimic theirs. Of course it is Armand who causes this tonal shift, as a character who is later revealed to have once been a child brothel worker himself.

Armand bringing up the sex workers who lived in the same building as Louis, who he thinks to reference and names respectfully, is the first instance of him showing a kinship with Daniel.

One moment that I found especially interesting between Armand and Daniel was when Daniel mocked the other by calling him a “rentboy” whilst rejecting the possibility of being turned into a vampire by Louis:

Louis: I’d give it to you now. A still hand, time to watch your daughters marry.

[The camera cuts to Armand who looks unsettled.]

Daniel: And divorce. And die. Save it for the rentboy.

Daniel is directly referencing Armand when he says this, suggesting Louis should turn him instead. I’ve seen a lot of people misinterpret this moment as a random insult which accidentally ends up hitting closer to home than it should, because of Armand’s history. Instead, I would urge people to think about it as one ex sex worker recognizing someone in a similar situation to one he used to be in and expressing his resentment. When he first met Louis, Daniel was in the habit of trading sex for drugs. He believes that Armand (who he believes is a servant names Rashid) is paid to allow himself to be bitten, a service which we are shown time and time again provides some level of sensual or sexual satisfaction, and sees his past self in the other whether or not actual sex is being traded. His insult isn’t harsh by chance because of Armand’s past trauma, it’s an intentional comment on the current situation. A reminder of what he once requested whilst offering sex as a trade.

Between the explosive fight where Louis ridicules his partner over his experience of sexual enslavement and the revelation that Louis killed many young men willing to trade sex for drugs, the series never shies away from being messy with these themes. Armand has a history of trauma from forced brothel work and a partner who was once a brothel manager, yet he is revealed to have been the manipulator in their relationship. The show doesn’t tell us what to think in the form of PSAs or moments where Daniel stares into the camera and gets into the ethics. The audience must rely on their media literacy to see what the sale of sexual services is adding to a characterization and how such a history might change their views and actions.

I wouldn’t watch Interview with the Vampire with the intent of seeing nuanced and realistic portrayals of people who sold sex throughout recent history, though aside from the fantasy elements we get some of that in the early first season. I would suggest watching the show for the questions it provokes about the sale of sex and how it relates to power and intimacy… and for the hot vampires.